Several political observers call the U.S. a corpocracy, which means a government controlled by corporations. Since corporate lobbying is more consistent and remunerative than other voices, the corpocracy accusation seems relevant. Politicians need money to get elected, but once in office respond to requests prioritized by lobbies. Campaign donations don’t change politician priorities as much as lobbying. Campaign donations buy consultants, ads, mail, press, a ground team. But voters still determine elections. Lobbying buys friends and influences those elected. Lobbyists offer legislators ways to manipulate systems, with prestige. They play with fancy lifestyles, good restaurants and entertainment, vacations and clubs. Most important, they promise future support, even in retirement.

None of this may be illegal. But a lobby group that offers support doesn’t need to say the reverse is also true. The politician can choose not to accept, and someone else gets the offer instead, a zero-sum game. The political problem isn’t campaign spending, but legislator corruption.

It sounds pretty nefarious, and hence corpocracy is not a neutral label. But corporate control is not absolute. It overwhelms government under certain conditions. Wise governance avoids those situations.

The U.S. “Founding Fathers” were not the noble Gods of civic myth and Mormon dogma, but they were sagely realistic. Power corrupts, and interest groups are self-interested. Like referees before a match, the founders decided to ensure lots of competition. At a time when valuable interests were in property and trade, they lacked tools to examine business collusion. Most property was land or, sadly, people, which needed government validation and protection. Trade operated in mercantile conditions, and needed government tariffs and security. Since legislators and judges would be owners and traders, the framers recognized government risked fusing economic and political power. To solve this dilemma, competitive government could force interest groups to balance each other’s influence.

Government competition needed structure. So the founders devised institutions — legislative, executive, and courts — to divide up the nation’s leaders. Each would check the other, and balance conflicting interests.

Divide and conquer, the British colonial technique, was first codified by Caesar, “divide et impera“. Several neighboring countries would be treated unequally, to create dissension and prevent alliances. Machiavelli advises rulers to divide enemy forces with internal suspicions. Napoleon divided opposing armies with clever tactics, and kept them separated. Cardinal Richelieu used French money and soldiers to keep Bavarian princes fighting, and Germany from uniting. Otto von Bismarck kept liberals, conservatives, and workers divided, to unite Germany under Prussian rule.

Unity was proffered by Benjamin Franklin as the only strategy to achieve national independence for American colonies in 1754. He illustrated this with a famous image, a snake cut into many pieces, with the phrase “Join, or Die” underneath. Franklin argued that the “disunited state” of the colonies made them weak, and unity would forge strength.

Years later, at the second constitutional convention, Franklin proposed a single, unicameral legislature. He’d come to believe in the wisdom of crowds, where emergent majorities would be just. But the 18th century’s elites saw mobs as the most dangerous colluding forces, not businesses or planters. Bicameralism would limit populism to the House, while keeping landed interests in the Senate. Jefferson noted that only the President had a national perspective, but this was feared. Legislators wrote laws, which the executive consented to or vetoed. The legislature could overrule vetoes with a super-majority. The legislature’s laws, and the executive’s implementation of them, could be questioned in courts, and overturned by justices. Justices themselves needed executive nomination and the legislature’s majority approval.

The founders didn’t trust self-interested voters or self-interested government. At every turn the constitution drafters tried to offset one group’s advantage by another group’s oversight, funding control, or approval. Even in a democracy, voters would find it difficult to coalesce as oppressive majorities. It was James Madison, pondering the newly independent country’s constitution, who first broached the possibility that business interests could also coalesce and usurp government power. He thought he’d found a loophole, though, for the U.S.. “With certain qualifications”, he explained in a letter to Thomas Jefferson, the republic could use divide and rule to “be administered on just principles.”

Property ownership, he wrote, will always be unequal, because of the “very protection which a free Government gives to unequal faculties of acquiring it. There will be rich and poor; creditors and debtors; a landed interest, a monied interest, a mercantile interest, a manufacturing interest.” This, he felt, led to problems.

On the one side, the poor, indebted, and landless, a great number, could coalesce around a populist despot with a Robin Hood message. On the other, a group sufficiently wealthy and clever had the potential to monopolize government, through manifest or latent corruption. This second phenomena was a problem for princes, according to Madison. Inequality would undermine democracy primarily through despots appealing to thoughtless crowd mentality.

Madison did not predict that the most unequal group, having the most wealth, could get so much power they became a tacit royalty. He had seen democracy emerge out from royalist conditions, and assumed the mob’s chaotic nature prevented it from following a path back in.

It was the U.S.’s expansive geography, still almost unimaginably large in Madison’s day, that most reassured him. The wealthy remain divided if they have opposing interests, and Madison considered the nation’s varied climates, soils, and continental positions a blessing that made this possible. Wealth gets generated in different ways in different environments. Each method would demand protection, and a single interest group could, at most, only dominate state-level politics. Despotic appeals to the poor were also checked by distance and different cultures. In 1789, slave-owners were not paranoid about Northern abolitionism coming south to persuade poor whites to reject planter overlords; they needed the arrival of trains to trigger that fear. Madison thought that as the union expanded across an entire continent, the U.S. had a unique capacity to balance divergent interests at the federal level.

* * *

Madison proved prescient, yet wildly optimistic. Within two generations, the interests of slave-holders would emerge to trump all political debate in southern states. The federal structure could not control these oppressors through legislation. Having many states proved an insufficient barrier against despotism, if half coalesced around a single issue. Further, western expansion became the focus of south/north disunity. As people diffused across the continent, each new state became a battleground about slavery.

Checks on government procedures became tools of a unified minority that maintained their regional power, rather than balancing different groups in grand compromise. The founders did not understand how economic forces could overpower national interests, something the public recognized itself, less than three decades after George Washington left office.

The U.S.’s internally divided governing structure was threatened by despotism, because the public feared special economic interests. The seventh president, Andrew Jackson, grasped all the power he could, ignoring the Supreme Court to make the Cherokee Indians walk 2000 miles (he mocked Chief Justice’s injunction, saying “let him enforce it.”) Jackson’s very popularity was that, in the words of a contemporary, his despotism was “interpreting the Constitution, and administering the laws, for the benefit of the many instead of the few.” This was the opposite of what the writer considered typical despotism, which benefits the few on the backs of the many. But it’s probably Madison had in mind, when he warned that a majority with shared interests has little “to restrain them from oppressing the minority.”

Jackson’s despotism emerged along with, and because of, economic change. In an era when the constitution was not yet sacrosanct, he was elected to address economic problems it failed to foresee. A new generation believed financial institutions could overpower government, as states could overpower the federal union. Jackson won a viscous presidential campaign, warning voters that bankers corrupted and ruled by money control. He fulfilled a promise and ended the Second Bank of the U.S.’s charter, the era’s central bank. The public believed this bank secretly managed the economy. It symbolized the 19th century’s growth of global economic forces that 21st century citizens still struggle to come to terms with.

His administration had a two-pronged strategy: undermine financial powers that were too big for ordinary folk, and unite the states in the defense of all Anglo-American men, rich or not. The dynamics of divided government, so cleverly crafted two generations earlier, were too flimsy to prevent his majority coalition. Madison’s geographic hypothesis assumed different regions checked each other’s interests. But racism and the common interests of slave-holders, whether located in coastal swamps, pine barrens, Piedmont or floodplain, united southern states behind Jackson’s white supremacy. Northern farmers and craftsmen, a great group of little kings, lined up behind Jackson’s anti-bank rhetoric. The public elected a despot to suture together a fraying polity, by dethroning bankers and ethnic cleansing.

Despotism doesn’t solve long-term problems, only delays them. Until political structures form to control political monopolies, and channel them productively, societies lurch from crisis to crisis. Jackson’s presidency marked the assent of a new kind of economic power that might challenge fair government. It would take nearly twenty more presidents before laws adapted to this new condition.

* * *

The Civil War marked the ultimate geographic division of the U.S.. Lincoln imposed martial law during the war, which Congress, with only northern and western states seated, authorized. The logic of divided government lacked immediate consequence in a nation about to dissolve. But in 1866, a year after the war and Lincoln’s assassination, the Supreme Court ruled martial law unconstitutional. Once somewhat mended, the union turned away from a half-century of geographic self-interest. The constitution’s divisions started to function. Congress and the Executive squared off in 1868, as President Andrew Johnson was nearly impeached.

The Gilded Age overshot anything the U.S. Constitution authors’ imagined. They dreamed of agricultural republics, but starting in the 1880s, the U.S. was about enterprise. Through the previous 18th century, political parties were barely tolerated as a passing fad. President Washington’s farewell address, like President Eisenhower’s 150 years later, served to decry an institution usurping government control. For Eisenhower it was the military-industrial complex. For Washington, it was political parties, which ” may now and then answer popular ends,” but with time “become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people.”

Soon enough Americans had discovered the magnetic pull of party identification, that could unify strange bedfellows on political teams. After the civil war politics became a national sport. The war had mixed people from all over the country in big operations. A Massachusetts unit flush with fishermen would get posted next to some West Tennessee miners, who were next to Minnesota German peasants. They differed, but more surprisingly they agreed on tariffs, or railroads, or how to forecast winter. This stitched together political teams. They also invented new rules for playing ball, so that Illinois boys who had long arms could throw hard, and New York dock workers could hit far, and speedy Vermonters could steal bases. After the war political parties were confident in shared identity, and ready to compete. It was also era of the world’s first athletic league, where teams had fans that were passionate partisans: 1871’s National Association of Professional Base Ball Players.

Wealthy financiers took advantage of partisan mud fights to pay off legislators (and baseball owners took advantage of partisan gambling to fix games). Mass immigration and urbanization generated party machines whose spoils systems payed voters. Southern revanchists took over Democrat party control to prevent African-American voting. Endemic political corruption turned the process of government by checks and balances to government of checks and bank balances. Government’s three branches were often subservient to monopoly capitalism. New labor unions were crushed.

By 1900, however, civil service reform drained much corruption from the executive branch, which slowly evolved regulatory capacity. Previous laws passed in name only began to get enforced, including the 1890 Sherman Anti-Trust Act. Historians show it was initially a sop to small businesses, so they would support higher tariffs. Government used the Act sporadically over the next decade, often against labor organizers. It wasn’t until Theodore Roosevelt’s administration, after McKinley’s assassination, that the U.S. Justice Dept. used it actively. Sherman prevents cartels from restricting trade, which keeps competitors from entering markets, and pushes prices higher than otherwise. It made cornering a market a felony, unless it occurs because of a product or business’s inherent superiority, or by accident.

The late 19th century U.S. economy fostered monopoly control of steel, sugar, farm machines, and railroads. Monopolists drove down wages, and their market domination spread low wages through the economy. Progressive activists challenged corrupt politics and monopolies, and gained political force. But the Supreme Court rejected several government antitrust suits. The Panic of 1907 marked a watershed, as unregulated trusts, which managed monopolist wealth, caused a stock market crash. Roosevelt had successfully broken up railroad cartels, but in 1907 he took on a behemoth, the American Tobacco Company. The case took four years to wind its way to the Supreme Court, where Roosevelt’s successor, William Taft, had placed a conservative as Chief. But the era’s tenor was shaken by monopoly scandals, and the Court ruled against American, splitting it up. It announced another ruling the same day, one even more memorable, against Standard Oil.

The rise of urban populations demanded lighting fuel, which gave birth to the greatest antitrust battle. Standard Oil leveraged capital and power to become the biggest corporation in U.S. history, before or since. Ida Tarbell, a wildcatter’s daughter with keen intelligence and sense of justice, spent years unlocking Standard Oil’s skeletons. Her cool, yet shocking exposes rocked the nation. The Justice Department rode this great wave to overcome corporate resistance and make Standard Oil the Sherman Act’s test case.

U.S. anti-trust law expressly states its goal is to protect consumers from unfair business restrictions on competition. This invites narrow economic analysis. But when the Sherman Act was passed, Congress and the American press discussed monopoly’s pernicious impact on small-businesses and politics, not just consumers. When it got enforced, it was because Standard Oil bribed legislators to advance their interests, to change boundary lines or transportation rights. They bribed judges to ignore valid prior claims, in the process destroying small businesses. Standard’s immense power extended beyond economics into politics, and that touched off the greatest firestorm.

Standard Oil, its reputation fatally undermined by Ida Tarbell, was broken up. Of its many pieces, several recombined recently, including Exxon-Mobil, the world’s largest company by revenue. If it hadn’t been broken up, Standard Oil would be worth more than $1 Trillion today. It would compete with Australia or India in terms of total wealth (GDP).

Tarbell wasn’t the only thorn in Standard Oil’s side. Another was Kenesaw Mountain Landis, a Federal Judge named for a Civil War battle ground. He grew famous when he levied an enormous fine on Standard Oil for corruption, and became Baseball commissioner to clean up the game after the “Black Sox” scandal. A man of his time, Landis was obsessed with control. Where companies or baseball teams exerted too much control, they destroyed “public confidence” in national institutions. Hoarding products, whether oil or talent, didn’t just cost consumers of fuel and sports more money. It was immoral, and caused the public to question corporate and league integrity. Over time, doubt would undermine behavior, and corruption would spread.

* * *

The founding fathers had no foreknowledge of industrialization. Marshall’s Supreme Court (1801 to 1835) fished the Commerce Clause out of the constitution, to hinge early corporate regulation on. After public outcry drove antitrust legislation, enforcement, and Senate reform, it was up to progressives to establish effective business oversight. Woodrow Wilson, a progressive elected in 1912 when Roosevelt split Republican support, launched the Federal Trade Commission and the Federal Reserve System to establish governing rules. It was under his administration that the Clayton Antitrust Act girded monopoly law.

Many of Wilson’s campaign speeches, collected in the 1913 book “The New Freedom”, focused on monopoly’s political impact, rather than its consumer violations. His description of the era’s public policy corruption resonated with voters. If they were angry about high cartel prices, they were furious about monopolist’s corruption of government.

Wilson insisted he supported business that used acumen and innovation to gain wealth. But he spoke when most of the nation’s wealth came “from those sources which have built up monopoly.” These giant firms had their own self-interest to protect. “When I see alliances formed, as they are now being formed, by successful men of business with successful organizers of politics,” Wilson said, “I know that something has been done that checks the vitality and progress of society.” This was a far cry from the Constitution’s notion of checks and balances; instead of business interests checking each other, they checked the public’s interest.

The Gilded Age was tarnished. “One of the most significant signs of the new social era is the degree to which government has become associated with business,” said candidate Wilson. “I speak, for the moment, of the control over the government exercised by Big Business.” He specified “government and business must be associated closely. But that association is at present of a nature absolutely intolerable.” instead of government in control of business, their roles had reversed: “our government has been for the past few years under the control of heads of great allied corporations with special interests.”

To check this economic control of government, antitrust law was a necessary measure. But it was not sufficient. Wilson announced that legislation needed to move out of committees, dominated by special interests, into the whole chamber. He wanted transparency on the process, to inhibit lobbying effects. Wilson also favored direct election of Senators, up till then selected by their state assemblies, where graft occurred.

Antitrust policy was still the cornerstone of progressive efforts to defang beasts corrupting national politics. When corporations had such wealth and power, their mutual coordination became “vastly more centralized than the political organization of the country itself,” said Wilson. Finding that money buys political sway, businessmen “allowed themselves to think that the whole matter was a necessary means of self-defense,” otherwise lesser powers would fill the vacuum. They were facilitated by legislators who seemed blissfully unaware of their own corruption. “I am very much more afraid of the man who does a bad thing and does not know it is bad than of the man who does a bad thing and knows it is bad,” said Wilson, “stupidity is more dangerous than knavery.”

Alas, legislation to prevent corporate capture of government is difficult to draft, since good businesses may naturally enlarge and seek government favors. Progressives considered antitrust law a feasible way to prevent too-big-to-ignore companies and cartels, and antitrust’s apparent aim of protecting consumers made the measure politically feasible. Yet Wilson was clear: breaking up odious alliances was necessary, because government was controlled “by organizations which do not represent the people, by means which are private and selfish.” He didn’t pull punches: “We mean … the shaping of our legislation in the interest of special bodies of capital and those who organize their use.”

Muckrakers in the press detailed how business interests like Standard Oil corrupted Senator selections, to install their hand-picked Senators. Wilson drove through the 17th Amendment, mandating the election of Senators, ratified in 1913. Then the Clayton Anti-Trust Act, passed in 1914, empowered regulators to prevent monopolies from developing in the first place.

Wilson was the only American president who may have preferred a parliamentary system to the constitution’s setup. Although he wrote a five-volume history of the U.S., Wilson believed that Darwin’s evolution theory applied to government as well as nature (imagine his reception today!) Government needed to quicken its pace, to meet the demands of modern business enterprise. The framers deliberately slowed congressional efforts, using political inefficiency to manage different interest-group inputs. The dictum “advise and consent” describes how Presidents present general themes to congress, where details get written in different subgroups that jockey for influence, their final compromise facing the executive’s veto privilege. “Advise and consent” was a process to “divide and conquer” interest group demands.

By 1912, businesses extended beyond state lines, in Standard Oil’s case well beyond national lines. Madison’s expectation that continental geography would grow many different kinds of interests, canceling each other out in Washington, seemed pre-modern. With trusts or cartels, collections of businesses could concentrate supra-national power. They would command revenue streams larger than most states. Wilson wanted a faster, leaner government that could respond to these quickly evolving companies. In the end, however, antitrust law served to slow down corporate behemoths, which proved more practical than speeding up constitutional procedures.

With Standard Oil split, Senators elected, and antitrust law built and enforced, the threat of monopoly impacts on consumers, businesses, and politics seemed contained. Soon historical memory lapsed, though legal specifications remained. The political and social impact of corporate control diminished, to be taken up occasionally by insightful judges like Learned Hand. As the U.S. economy and population expanded, some attributed the 19th century’s antitrust concern to small-mindedness. People were uncomfortable with large scales, so they attacked big business.

The 19th and early 20th century antitrust focus was more than a concern about big size. At issue was control. President Jackson didn’t shutter the First U.S. Bank because it was big, but because it had outsize influence, according to its critics. Madison didn’t fear the size of government, but its concentration in too few hands. When Henry Brooks Adams uncovered Jay Gould’s cornering of the Erie railway, it wasn’t the size of the company that mattered, but the fact that it corrupted the presidential administration.

Companies can vertically integrate and control a product market, if they can restrict competitors in a production or distribution process. That can hurt consumers. But companies can horizontally integrate and control neighboring business sectors, which usually compete. Whether this directly impacts consumers, it can devastate public policy. When railroad companies bought up shipping firms, they reduced ship competition. Economists debate whether transport costs went up. Railroads expanded faster without boat company resistance to bridges. But the public, as the elected government, lost influence in shaping their nation’s landscape. Half a century later auto companies returned the favor and bought up railroads, so they could rip up tracks. Maybe that too expanded auto production and lowered costs. But the cost in public policy options was severe. Another half a century finds the nation needing light rail, without the option of existing lines.

* * *

According to Richard Hofstadter, 1914 marked the high-point of public anti-trust sentiment. Gilded age monopolies were huge and visible, literally overwhelming landscape and workforces. But as the U.S. population swelled and expanded across country, industrial behemoths were left behind in specific areas like Detroit and Pittsburgh. A German could escape the industrial Ruhr, but he’d have a hard time hiding in Bavaria, Prussia, or Berlin. An American could flee Detroit, and start a new life in Missouri, Idaho, or California.

World War I left Americans tired of politics and excited by opportunity. They didn’t understand Europe’s suicidal conflict, though the 1918 flu epidemic suffocated hope at home. War exhausted Europe profoundly, destroying a generation, and investment interest turned on the U.S., where a cynical euphoria took hold.

Technology changed more suddenly than any time in history. Space was conquered by auto, plane, and phone. Change was different this time, faster to occur, and faster to experience. Some felt giddy, others tempted, and many were uncertain and afraid. Provocative and challenging, new technology made people appreciate big business’s apparent know-how.

In the 19th century railroads and oil had stimulated massive developments, but accreted over time. The first train were pulled by horses, then small steam engines pulled horseless carriages, then little trains, then bigger ones. At least one human generation grew up alongside, at the same pace. Petroleum replaced wax and oils in simple lights, long before significant use in cars. It advanced as city dwellers sought oil lamps, but people had used artificial light for ages.

Both railroads and oil companies grew large because they were commodities. Railways crisscrossed every few miles of the Midwest and northeast, their marginal cost very low. Oil was liquid mining, and replaced coal or wax. Cornering their supply was profitable, but unnecessary for efficient production. Their monopolies hurt other businesses and consumers, who could imagine different arrangements.

Then the 20th century hit, with unimaginable change.

In 1900 people believed cities were doomed to horse manure asphyxiation. Linear population and manure projections showed that, by 1930, Manhattan would be buried up to three stories high in the stuff. But within a decade cars appeared, Henry Ford introduced the assembly line, and by 1912 there were more cars than horses in New York. Horses disappeared from city streets in the 1920s.

Meanwhile, up through 1910 most people thought airplanes were a fraud, a Barnum and Bailey trick for suckers. They were often scared when they finally saw one. But by the 1920s, people were sending U.S. Airmail regularly. They loved the service, admired pilots, and read about the airborne wealthy. KLM, the Dutch national carrier, was chartered in 1920.

In 1900, people scratched their heads when they saw someone shout into a box on the wall. Telephone use grew to 5.8 million in 1910, then 15 million in 1924. Phone booths grew common, and anyone could make a call.

One generation barely got out of its teens by the time these new technologies went from introduction to mass use. Technology moved so fast people didn’t know what to expect.

In 1921, Congress passed the Willis-Graham Act, which gave AT&T an exemption from antitrust law. The government agreed with AT&T that a monopoly would unify and spread service. People wanted phones to socialize, and liked the ubiquity of a single vendor. In return, the government regulated service cost and mandated rural telephony. This marked a shift away from the anti-monopoly mood of the previous decades, as well as a new view of regulation. Rather than big business controlling government, government would domesticate it.

Airline transport developed via the four companies authorized to fly domestic mail (Eastern, United, American, and TWA) and one granted international rights (Pan Am). Government regulation offered lucrative contracts and unchallenged routes; regulation also enforced safety and mandated destinations and service, which passengers demanded. In this case, the technology sharply violated everyday reality, so people expected rules, rules, rules. An oligopoly proved manageable for compliance.

The shock of new technologies, and a different political wind, made antitrust concern recede. Assembly line industries seemed to demonstrate the benefits of economies of scale. GM purchased competing companies without raising antitrust concerns until 1941. The nation’s leading manufacturer, it escaped the cost-benefit web that government spun around AT&T and the airlines.

Trains and oil needed to be available, affordable, and safe. Monopolies threatened affordability, corruption of government could reduce safety, and only regulators might ensure availability to far flung places. On the other hand, people wanted cars to provide identity and status, performance gusto, and pleasure. These are not items a regulator can provide. GM’s many brands offered identity, with powerful engines and seats fun to ride in. People needed trains and oil, but they loved cars.

If phones and planes awed the public, mighty manufacturers impressed government. GM stood highest on the U.S.’s commanding heights, which in the 1920s and 1930s referred to a country’s most important industrial production. Lenin used the term for key economic sectors reserved for state control: steel, tractors, and arms. But in all capitals, authoritarian or democratic, governments believed heavy industry produced economic and military security.

GM’s genius, personified by its president Alfred P. Sloan, was to understand that management, not physical plant, determined industrial strength. By the 1930s the company built more cars than anyone, replaced trains with its buses, replaced steam engines with its gas and diesel locomotives, made aircraft, and had the country’s biggest workforce (unionized after 1937). The world’s largest industrial enterprise rested on the shoulders of managers, armed with industrial management degrees, pioneering statistical analysis, and given semi-autonomy to demonstrate competence.

Educated technocrats ran things in Washington, D.C., too. The U.S. elected an engineer, Herbert Hoover, as President in 1928. Hoover was part of the Efficiency Movement, an outgrowth of the progressive era that was more technical and less political. The Movement wanted experts to solve social problems, often through business/government partnerships. The Great Depression cut short Hoover’s career, but the next president, Franklin Roosevelt, shared Hoover’s belief in these alliances.

GM was viewed as the most efficient big business, as America’s weightiest industry. This gave it privileges, like avoiding antitrust concerns. While the Soviets believed big factories had the equipment and workers needed to shift quickly to wartime footing, the Americans believed that GM had the necessary management for rapid wartime development. The Americans were right.

Preparing for war in 1940, Franklin Roosevelt convinced GM’s president to resign and head U.S. wartime production. Commanding heights philosophy paid off, as GM produced more military equipment than any entity in history. Allied armament, vehicle, and aircraft superiority was a key component in victory. Down the chain of command and out into the battle arenas, other managers deftly improvised and organized, keeping shipments flowing through fire and blood. The World War II U.S. supply chain, run by GM managers, created the biggest industrial flow in human history.

Antitrust became less important after 1814 in part due to technological impacts. Inventions that shocked or amazed, like aircraft and telephones, were seen as needing unified business control. America’s giant industry, automobile manufacturing, awed government for its heavy potential. It got an antitrust pass. Government could demand these three new technologies to sacrifice for the common good. Aircraft had to deliver mail, telephones had to reach distant people, and GM had to manage wartime supply change, as government demanded. In return, they could monopolize.

* * *

Another shift in regulatory thinking took place because of the Great Depression. Antitrust’s purpose was reconfigured, and applied to the financial sector.

In 2013 the word “pivot” gets attention in the lexicon of strategy. President Obama’s administration capitalized on the word’s simplicity and sportiness to conceptualize strategic reorientation.

The Great Depression’s overwhelming consequences made any successful administration pivot and pursue new economic policies. Among Roosevelt’s legacies, his pivot from antitrust to financial regulation was key. A pragmatist, Roosevelt bore allegiance to no policy that threatened more unemployment, and would try most options that offered growth. Business leaders tried to influence politics, but they could no longer promise laissez-faire prosperity.

The fear of size was less relevant, when being big meant you were called on to share government’s duty.

A financial crisis had been a reason for the Justice Department’s timing in going after Standard Oil, whose trusts were implicated in ruined banks. The 1907 panic also led to the Federal Reserve’s formation. It was hoped this might curb speculative frenzies, if financial regulators limited money supply as they overheated. Instead, the Fed let the roaring 20s boom, and seriously limited money supply after the crash — precisely the wrong time to tighten liquidity.

The Depression was caused by banking interests that abused their missions, unable to resist leveraged, speculative riches. The roaring 20s were fueled by booming land and stock values. Commercial banks spread into securities underwriting and launched national retail networks. No single bank held monopoly positions, but they were Janus-faced. By 1928, 591 commercial banks engaged in underwriting. Banking requires knowledge of customers and borrowers. Securities underwriting requires knowledge of companies and markets. Unfortunately, warranting securities that hide downside risk, and exploiting bank customer vulnerabilities, is a profitable combination.

Roosevelt’s administration focused on cleaning up bank conflicts of interest, not antitrust. It was not “divide and conquer”, but protecting society by protecting banks from themselves. The most important outcome was the Glass-Steagall Act, which barred FDIC insured banks from underwriting securities, and investment institutions from using ordinary bank capital.

Business sectors need governance, rules and conditions. Good government listens to businesses, to enact the rules and conditions that enable business success. But neighboring business sectors usually need or thrive under different rules. So good government must balance both sectors’ needs, curbing the benefits to one if they injure the other too much. Commercial bankers want government to insure their customer accounts, and government can do so. Investment banks want laws to form security markets, and the government can provide them. But when commercial and investment banks are one, they want government to insure security markets as if they were customers.

Glass-Steagall prevented this. It set up a wall between banking and speculative finance. This began an era. “Good fences make good neighbors” replaced “divide and conquer”. Robert Frost’s line was in a 1914 poem called Mending Wall, about a social strategy Frost’s neighbor used to fence off conflict. With Glass-Steagall, the Roosevelt administration fenced off conflicting interests.

From James Madison to progressives like President Wilson, “divide and conquer” animated anti-corruption and pro-democratic solutions. In 1910, citizens could conquer corruption and exploitation by busting hegemons and power centers and fracturing big trusts . Frost, a New Englander in a close-lipped community, reported that people stayed true to their business if simply kept separate. Citizens debated in town halls, perhaps about the “commons” (community property). They found a decent balance by remaining properly divided. Good fences kept them happy.

Glass-Steagall’s good fences separated banks and speculative underwriting, so each focused on their work, and not greener grass over yonder. But unlike “divide and conquer,” which is easy for humans to play, “good fences” require good characters. Greed and avarice break down barriers. In the 1930s, bankers and Wall Street had been humbled by the Great Depression, and made easy to fit in like neighbors. But Frost’s poem is pessimistic. “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,” he writes. Frozen ground breaks its rocks. Hunters kick them over, “to please the yelping dogs”. Without an annual mending, they disappear.

Glass-Steagall’s fences would hold 30 years before they broke, and over 50 before they got kicked over.

* * *

Technology, depression, and war were “shocks” that pushed antitrust issues into the shadows. A core group of wealthy business leaders hated antitrust as much as they disliked Roosevelt. Over the next thirty years, they would narrow antitrust domain further.

Franklin Roosevelt put a reformer, Thurmond Arnold, at the head of the Justice department’s antitrust division, not to protect legislation, but to stimulate economic growth. The Clayton act’s orientation towards consumer protection fit the technocratic mindset. World War II left the U.S. public complacent as technocrats regulated a corporate sector that offered mainstream affluence. Labor unions grew flush with ex-GIs, and powerful. Sometimes ex-GI police, called on to suppress Veterans of Foreign Wars brothers on strike, refused. Many companies accepted the Keynesian logic that decent wages produced consumers with disposable income.

World War II changed the U.S., particularly those who fought or worked its factories. They were the first American generation to believe that government could manage affairs effectively, that central planners made reasonable decisions. During the war people got work in private companies that made things for the government. They served in units that produced results, in war and at home. Many, if not most Americans expected the war’s end to usher the Great Depression back in. But Keynes was vindicated. By sufficiently stimulating the economy, pumping in vast resources under government supervision, the economic engine started running on its own. A war-time deficit of larger scale than any since was payed down in a few years

The “greatest generation” came home, found work, and organized. For seven or eight years, the US had many massive union strikes. Buy most strikes ended peaceably, with compromise. Companies grew less fearful of unions, and workers less worried about unemployment.

The GI Bill shoehorned a grizzled, no-nonsense tribe into management, administration, and the professions. The federal government provided subsidized mortgages for young families in the suburbs. The government was credited with understanding economic management, and its expensive foreign policy, very militarized, was supported by high taxes. Both Democrats and Republicans, eager to show their patriotic bonifides, kept most tax cuts off the table.

Neither unions nor corporations had a monopoly on government. Political historians credit the post-war benign economic prosperity to this balance of power, which checked either side from domination. GDP and personal incomes grew, but wealth spread across income strata. The “Founding Fathers” appreciated this division dynamic, but they had no way of predicting the modern corporation or union. The post World War II balance was struck by macroeconomic forces and historical conditions, not constitutional planning. But a balance of powers represents half of the “checks and balances” equation.

Perhaps helped by business and labor balancing, the U.S. government, from World War II to Vietnam, drifted closer to Wilson’s parliamentary ideal. Political parties contained potential demagoguery, and presidents engaged bipartisan strategies, helped by the Cold War’s overarching dynamic. John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson were legislators who became executives, as prime ministers rise from parliamentary ranks. Johnson, in particular, was an American counterpart to Clement Atlee, the British Prime Minister who established its National Health Service, public pension scheme, and more. Johnson’s Great Society programs were passed with similar fanfare, as his party dominated the U.S. Congress like Atlee’s did the U.K. parliament.

Arnold’s antitrust division grew as well, in scale and professionalism, but enforced law quietly. With bipartisan support, it mitigated monopolies in aluminum, tobacco, and electronics. Yet nothing is permanent; the latter case, in 1959, revolved around General Electric, and started a business reaction.

GE was forced to admit it fixed prices, and this hurt its reputation. During the 1940s and 50s, GE had been the big business most able to suppress unions, and one of the best at burnishing its public image. In the wake of the price fixing penalty, GE pivoted. Along with unions, government itself entered their cross-hairs, a critical decision. While the antitrust division continued to limit monopolies, GE focused on limiting government. Their public relations figurehead, Ronald Reagan, entered politics.

* * *

In the 1950s, a group of University of Chicago economists began their attack on antitrust. It would prove fruitful in narrowing thought.

Judge Richard Posner, a Chicago Law professor and fan of the university’s economics agenda, reviewed the origins of Chicago’s antitrust critique. He dates it to economist Aaron Director’s discussions with colleagues in the 1950s, and notes that “because of Director’s close personal and professional associations with Milton Friedman, it is common to think that Director’s antitrust analysis was the product of conservative antipathy to government intervention in the economy.”

Friedman, the iconic monetarist and libertarian, or, as his son defines it, anarcho-capitalist, established Chicago’s economics reputation. A central figure in Fredrick Hayek’s Mont Pelerin society, Friedman shared with Hayek the belief that government regulation led to “serfdom,” i.e. totalitarian rule. Hayek’s Road to Serfdom was savored by Americans like Friedman who opposed the New Deal (Friedman allowed that its job creation programs were OK, perhaps because New Deal agencies hired him for a decade). Mont Pelerin’s neoliberal economic views resonated with corporate families like the Du Ponts, who themselves believed Roosevelt inteded to impose communism. The convergence of economic theory with conservative corporate leaders led to think tanks like the Heritage Foundation and the American Enterprise Institute [AIE].

AIE’s founders included Eli Lilly, guilty of price fixing insulin (an antitnrust violation); General Mills, at one time atop the Minnesota “Flour Trust” which controlled 97% of U.S. flour production, broken up in the 1930s; and Bristol Myers, a member of Drug Inc., a cartel that between 1928 and 1933 controlled much of the U.S drug industry. Antitrust was a dirty word among these corporations, and an insult to the free market among Mont Pelerin economists. Aaron Director passed the message to his colleagues and students.

Posner prefers to believe that Director’s antitrust opinions “resulted simply from viewing antitrust policy through the lens of price theory.” Or price theory was developed as a lens to project neoliberal views, including opposition to antitrust.

A 1951 paper written by Director’s colleague John McGee was a critical turning point in antitrust’s containment. In a questionably researched yet seminal article, McGee claimed that the granddaddy of all antitrust cases, Standard Oil, was a mistake. This view would inspire Judge Robert Bork and Judge Posner to write highly influential condemning antitrust, 20 years later.

After culling the trial record for vagaries that might throw a tender light on Standard, McGee announced “I can not find a single instance in which Standard used predatory price cutting to force a rival refiner to sell out, to reduce asset values for purchase, or to drive a competitor out of business. I do not believe that Standard even tried to do it.” The final sentence was key, because an objective review of trial evidence shows Standard most certainly did predatory price. But McGee saw Standard’s leaders, especially John Rockefeller, as preeminently rational businessmen. If predatory pricing was irrational, Standard didn’t do it.

Today’s right-wing think tank industry hangs its campaign against antitrust on this idea. As a President of one of 40 state level, corporate funded, conservative think tanks wrote in 2012, “43 years ago an article was published that thoroughly demolished one of the most enduring myths of American economic history”. Though “some people blithely and irresponsibly ignore the message and continue to propagate the myth,” the article in question, McGee’s, showed the accusation of Standard’s predatory pricing was “logically deficient.” It couldn’t have happened, because it wasn’t logical.

Daniel Yergin, author of a monumental petroleum history, The Prize, investigated Standard in far greater detail than McGee, or any think tank pundit. Yergin wrote:

“Rockefeller and his colleagues had often instituted a ‘good sweating‘ against their competitors by flooding the market and cutting the price. Competitors were forced to make a truce according to the rules of Standard Oil, or, lacking the staying power of Standard Oil, they would be driven out of business or taken over.”

Christopher Leslie wrote a consise, precise debunking of McGee’s claim that Standard Oil didn’t predatory price. Leslie detailed how McGee misread, misinterpreted, or ignored evidence. Economists James Dalton and Louis Esposito reexamined the trial record, and found it “contains considerable evidence of predatory pricing. Simply stated, the Record does not support McGee‘s conclusion that Standard Oil did not engage in predatory pricing.”

Allan Nevins wrote a big, popular Rockefeller biography in 1940, and asserted the so-called robber-baron was an American hero. Nevins claimed a review of great man’s work found predatory pricing used only .01% of the time. Ron Chernow’s recent and more even-handed Rockefeller biography reviewed prior works and many original documents. Chernow wrote they were “so rife” with references to predatory pricing, Nevin’s version must be false.

In 1975 Ferdinand Lundberg critized Nevins idealization of Rockefeller, but said “so far nobody has conspicuously” followed in his footsteps. Lundberg wasn’t aware of McGee, and legal rulings remain surprisingly uninformed of anything other than McGee. Books like Chernow’s are criticized, not by fact checking, but because he missed McGee’s point about predatory pricing: “Rockefeller would have been foolish to employ it.”

Because this simple, tendentious idea has had great influence, it worth deconstructing. McGee claimed it was irrational to predatory price. Leslie examined each of McGee’s logical arguments:

1. If Standard priced below cost, competitors would bow out of the market, then return when Standard raised its prices back up.

Leslie notes firms have dumped goods in markets, gobbled up market share, eliminated competitors, then been able to increase prices. Standard Oil’s history is replete with examples, even in the trial record. A more recent example, a favorite story in the 2012 Presidential campaign, concerns Solyndra, a solar energy company given government loans in 2009. China’s state-supported, inefficient, but cheap solar panels flooded the U.S. market in 2010. Priced below variable manufacturing costs, they bankrupted Solyndra and other U.S. firms. When tariffs were imposed on China’s solar exports by the U.S. and Germany, their price increased. After a shakeout caused by excess production capacity, China’s solar sector will probably further raise prices. But they have shaped the U.S. market for their products, by eliminating advanced technology competitors like Solyndra. According to McGee, Bork, and many conservative think tank fellows, this is unthinkable.

2. If Standard priced below costs, it would get huge market share. Then it would be losing hand over fist, selling so much so cheap.

Leslie shows how McGee underestimates Standard business practices. The company monitored every barrel of oil sold by independents in the U.S., aggregated by territory managers. Standard’s employees surveyed freight agents, distributors, store owners, and any buyers capable of purchasing from competition. They spied and bribed, and information fed back to HQ. Standard could target prices at specific places, even specific buyers, keeping competitors it attacked manageable. But sorting customers so cleverly had a down side: existing customers disliked when their neighbor got a better price. So Standard set up bogus companies, with different names, to sell to competitor’s customers, while it charged its customers the regular price. Standard learned to use bogus companies for most of its dirty work.

China’s surveillance and policy apparatus shows another form of slicing and dicing populations with monitoring, silencing some very discretely, while avoiding overt approbation. Given Standard’s scale matches the economies of many nations, its not surprising that a large country would exhibit some of its tactics. It’s interesting these tactics are dismissed by right-wing antitrust scholars, who find them odious in China.

3. Why would Standard lower prices, if it could just buy out competitors? Given its wealth, it had the capacity to do so. To me this seems the most relevant of McGee’s points, though Leslie finds it the least. Microsoft’s historical rise involved acquisitions of many smaller competitors, and Google has followed this model. In past decades companies like Teledyne grew from many acquisitions in the 1950s and 60s, and American Can in the 1940s. But Bill Gates is no John D. Rockefeller. Companies like Microsoft and Teledyne (an aerospace manufacturer) depend on intellectual effort. They benefit from acquisition because it brings high-tech intelligence and knowledge on board. Standard Oil, however, didn’t need more oil men clogging up its hierarchy, and the product wasn’t rocket science. Buying out an oil distributor provided buggies, warehouses, and shipping platforms, much of it unnecessary after consolidation.

Posner, in a paper differentiating himself from “diehard” Chicago school anti antitrusters, wrote that he found McGee’s third point lacking. A company wants to buy out competitors at the lowest price, “and that price will be lower if it can convince them of its willingness to drive them out of business unless they sell out on its terms. One way to convince them of this is to engage in predatory pricing from time to time.”

Standard Oil was broken up for many reasons, but as case law its primary illegality was predatory pricing. Tarbell and others documented many cases where Standard faced a competitor, cut its prices below cost, and presto, competitor gone. Immediately after, Standard would yank its prices back up high. But the Chicago School found this argument insufferable. Not because facts were wrong, but it failed to follow economic logic.

* * *

George Stigler, also a Chicago school economist, refined an economic concept with roots in progressive ideas into an attack on regulation, in a 1971 paper called “The Theory of Economic Regulation”.

“As a rule,” Stigler wrote, government “regulation is acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefit.” Thus he resurrected an economic idea from the progressive era, but shifted its focus.

As described earlier, Madison obsessed over small groups usurping governance. President Jackson rode a heady tide against financial control of government policy. Progressives, from Tarbell to Wilson, were motivated by private influence on public policy. Economists came late to the game, led by Thorsten Veblen. He described government as a “department” of organized business, so closely aligned were the interests of executives and elected officials. Richard Ely and John R. Commons, other economists of Veblen’s era, (the late 19th, early 20th century), outlined a model of how business networks systematically avoided or compromised state regulation.

But Stigler didn’t discuss how industries acquire legislators and policy makers. Capture Theory originally posited that producers in the economy, because they have wealth and are few, can concentrate influence on legislators more effectively than the mass of ordinary citizen consumers. But after Stigler, capture was rechristened “regulatory capture theory”. It wasn’t concerned with congressional committees that wrote laws, determined spending, and tax.

The Chicago school approach resembles “pigs in a blanket”, a hot dog wrapped in dough. Chicago economists take a libertarian worldview and wrap it in price theory. Libertarians view the state as a coercive, fundamentally unethical entity, and markets as moral and universally beneficent Price theory centers around two concepts: if prices go up, sales must go down, and if prices are too high, a competitor will enter the market and sell for less. From such acorns, might academic oaks grow.

Monopolies represent Ayn Rand business giants who seize and dominate markets through talent and will. Government regulations shackle business with petty chains. Worse, regulators are bureaucrats, people without freethinking imaginative spirit.

Step outside of the ivory tower, and look at most office parks. Tinted sealed windows conceal cubicle regiments, where people push papers or punch key pads. These are bureaucrats in the public sector, and entrepreneurial workers in corporations. The difference seems to be you can downsize, de-unionize, and get rid of pensions in the private sector, easier than the public. This is “market discipline,” a sword of Damocles that hangs over corporate employees, a reminder to give their best. It’s a “spare the rod, spoil the child,” mentality, popular in Central Asian despotic states, and other trouble spots. But what do I know? I haven’t been to business school.

The 1970s upended the Chicago school’s worldview. A giant U.S. monopoly, AT&T. was broken up, while its economic sector, telecom, was deregulated — by government actors. The Chicago school and its arch rivals, Harvard’s Institutional Economists, both provided theory to the government’s antitrust case, the deregulation and anti-monopoly parts, respectively.

After AT&T’s 1982 divestiture, competition increased, services improved, and most prices fell. So AT&T’s monopoly was quite inefficient, after all. At the same time, deregulation stimulated technology change. But without new regulations to protect the poor and seniors, and regulation of service architectures, political and technical barriers would have stalled progress. Chicago’s assumptions, or theory, were about 1/4 accurate.

Another moment of truth came in 1978, when Congress passed the Airline Deregulation Act. That ended the virtual monopoly of the Big Four and Pan Am. Like the AT&T case, it was a victory for both anti-monopolists and deregulators. Its immediate outcome was muddied by politics. Big companies suffered losses trying to match prices of new competitors. Deregulation also overworked members of the Air Traffic Controllers Organization, as loads increased 20%. The controllers went on strike in 1981, and President Reagan summarily fired them (Carter would have, too, but after a cooling off period). This saved the big airlines, for a time. With fewer controllers the FAA reduced carrier flights by a third, and new airlines were kept out of busy routes. After half a decade, a new air traffic control force was rebuilt, and routes opened up. Deregulation benefits spread.

Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer was a player in the airline deregulation story, as an assistant in the Senate transportation sub-committee. He went to a law and economics seminar in Chicago, perhaps in 1973, to hear Stiglitz explain that airline deregulation could never occur. Stiglitz believed his own capture theory: regulators would not permit deregulation. Breyer didn’t believe Stiglitz’s prediction, but was sure the airline oligopoly increased prices. Senator Ted Kennedy, chair of the sub-committee, took it on as a consumer issue. The reform path become merit-oriented. Economists, regulators, industry, and labor split among themselves, and the most efficient, logical perspectives dominated. Breyer notes the most intransigent opponents were airlines and regulators, as Stiglitz proposed. But key regulators defected, especially at the top. Industry publicity exaggerated consequences. But when Breyer and others interviewed airline leaders, they spoke truthfully, even against their own company positions.

The Chicago economic models of monopoly and regulation can’t describe these events. But then, perhaps no purely economic model can. Telephones and airplanes involve social, psychological, and regulatory levels that supersede economics. Humans are motivated by more than maximizing returns; sometimes they follow their conscience and question their assumptions.

After early 20th century progressives developed antitrust law, and broke up sprawling trusts, their vigilant spirit faded. The next decades witnessed great technological change, among which phones and planes shocked the most. The human species had spent thousands of thousands of years walking on earth, and talking face to face. Suddenly radical change occurred in one generation, and people were forced to understand they could fly and converse across continents. Government, industry, and the public agreed that such unbelievable things needed control, and weren’t suited to the chaos of competitive markets. Telephones and airlines thus entered into a government relationship, which protected their market shares, but limited and mandated their behavior.

50 years later, phones and planes were commodities, like railroads and petroleum in 1900. Men walked on the moon, and children often used phones as soon as they talked. The raison d’etre of airline and AT&T special relationships with government evaporated, and in Senate hearings and court cases this became apparent. Afterwards, economists looked for more sectors to break up and deregulate. But these didn’t catch hold of legislative or judicial interest. AT&T and airlines had unusual trajectories, launched with initial shock, but in two generations people got used to them.

Despite evidence that Chicago’s antitrust critique wasn’t correct, Chicago’s ideas gained traction.

In 1978 Judges Robert Bork and Robert Posner published, separately, seminal books attacking any semblance of social or political goals in antitrust. Their work had a significant impact on jurisprudence, hardening courts against antitrust plaintiffs. Law Professor George Priest, in an “An Essay in Honor of Robert H. Bork,” wrote: “Virtually all would agree that the Supreme Court, in its change of direction of antitrust law beginning in the late 1970s, drew principally from Judge Bork’s book both for guidance and support of its new consumer welfare basis for antitrust doctrine.” The degree of these judges’ conservatism can be “stunning” according to the New York Times profile of Posner. Bill Clinton, one of Bork’s Yale students, opposed his Supreme Court confirmation, amazed that Bork “even said federal courts shouldn’t enforce antitrust laws because they were based on a flawed economic theory.”

Posner reflected a perspective that questioned James Madison’s constitutional measures limiting interest-group or mob power. To Posner, the “many features of law and public policy designed to maintain a market system are more plausibly explained by reference to a broad social interest in efficiency than by reference to the designs of narrow interest groups.” The constitution, and societies generally, generate rules that serve the common good, not special interests, because economics says so. Madison, Jefferson, or Benjamin Franklin didn’t know a thing about rational choice theory. Ironically, this anti-originalist perspective is the opposite of Bork’s. To explain why Bork’s antitrust view was consistent with framers like Madison, the very judge nominated in his place, after Bork’s failed Supreme Court confirmation, stepped up. Judge Donald Ginsburg (who also failed to get confirmed, because he smoked marijuana), explained that originalism “has been refined and objectified to seek not the original intent of the Framers but the original public meaning of the words in the Constitution.” Thus, Bork claims to have discovered that Congress designed the Sherman Act as a ‘consumer welfare prescription’, even though none of those words is present in its legislative history.

In fact Bork was a libertarian who adopted originalism to serve his ideological purposes. As Senator Edward Kennedy said, in a speech opposing Bork’s Supreme Court nomination, “Robert Bork’s America is a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens’ doors in midnight raids, schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists would be censored at the whim of government.” Bork linked these libertarian opinions to an originalism that believes the US constitution’s writers wouldn’t have accepted these things either. This fundamentalism gets used by narrow-minded traditionalists of all faiths; before the civil war slavery’s defenders pointed to Biblical verses that permit slave holding.

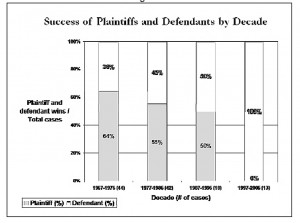

Bork left the judiciary to serve in the American Enterprise Institute, which experienced a ten-fold funding increase after Lewis Powell’s memo. But as Prof. Priest claimed, Bork’s antitrust influence continued to impact courts. The following chart shows the Supreme Court’s antitrust rulings over a 40 year period.

4 columns: 1967-1977, 1977-1987, 1987-1997, 1997-2007

The chart is from Priest’s laudatory essay on Bork. By restricting antitrust concepts to the narrowest possible economic context, antitrust law was eviscerated There’s no doubt that economists played a role, particularly the Chicago School of neoliberal economics. Judge Posner has taught at the University of Chicago Law School since 1969. He co-writes a blog with Chicago’s economist Gary Becker. Posner attacked the broader social purpose of antitrust, but left the final assault to Bork and his followers.

* * *

After the left’s apparent success at capturing government policy in the 1960s, Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell, a Nixon nominee, penned a famous “letter to business.” It explained how government was now their biggest antagonist, and offered a road-map to taking it back.

Many companies unified in support of the new conservatism. Powell’s strategy was clear: unify business voices behind shared legislative interests. The technocratic era evolved to an economic frame of reference. The anti-trust idea became stringently economic. According to Powell, anti-trust needed to be trimmed to “economic realism, rather than nebulous and varying legal concepts.”

This insight was critical. Business had to eliminate any hint of coordinated, monopolistic power, if their goal was to massively coordinate business power. Antitrust was already bereft of what Woodrow Wilson or Learned Hand had seen in it. But a hundred major corporations uniting in shared lobbying power — that specter put even Standard Oil’s weighty influence to shame.

GE provided a template for mass propaganda. While at GE, Reagan’s job was to entice employees with a vision of the good life, free of organized labor’s conflicts. If it worked at GE, it was ready for prime time. Free-market economics, spearheaded at Chicago University, produced a template for judicial change.

By the late 20th, early 21st century, business had brought government under their control. Today, powerful money girds populist anxieties and weakens the ties that bind us. Hacker and Pierson’s The Winner Take All Society tells a cogent story of how business community captured government. They emphasize that weak unions no longer check corporate power. I agree. But they call for a return of union strength to rebalance today’s political economy, which is understandable, but doesn’t reflect the potential inherent in the U.S.’s long arc of resistance political control.

According to Hacker and Pierson, the 1960s ended with youthful idealism and selfishness intact but under fire. Watergate stamped government as objectionable, and economic stagnation was pinned on unions, or as the price of discontent. Idealists splintered into interest groups. The left no longer focused on wages and job security, but on environmental, gender, and ethnic rights. Instead of striking for wages, people marched for South African divestment and nuclear disarmament.

The big wave of left-wing energy, according to Hacker and Pierson, didn’t peak in the 1960’s; it crested in the Nixon and Ford administrations. That’s when EPA, OSHA, and other federal and state bureaucracies developed. Democratic party activists bypassed big-wigs in back-rooms, and state primaries actually determined the party’s presidential nominees. The first and most dramatic was McGovern in 1972. Earth Day 1970 spawned environmentalism. Congress passed the Equal Rights for Women amendment and sent it for state ratification in 1972.

Meanwhile, and largely unobserved, big business abandoned the post-war status quo, where union and government demands balanced corporate calls for fiscal and monetary contraction.

Hacker and Pierson’s story side-steps Reagan’s influence, by pointing to 1978 as the year corporate lobby power flexed its significant money advantage. During the Carter administration’s mid-term election, the south/southwest’s reactionary movement galvanized under the flag of Goldwater Republicanism. Corporate elites bankrolled an unholy alliance of evangelicals, “libertarians”, and segregationists, who sent politicians like Newt Gingrich to Congress. Bipartisan support for consumer and workplace protections vanished under a lobbyist flood, their record numbers engulfing the Capital. Democrats, including Carter, assumed this was a one time surge they could manage with temporary compromise.

Instead, it opened a new era.

I would note that many who are outside corporate leadership, including economists, don’t appreciate the inherent paranoia of business leaders. Its a miracle that a business survives and grows. Executives must pretend otherwise, but they know they can’t predict the future. Many are aware that corporate culture inhibits innovation, that merciless internal competition for promotion undermines business development. They know corporate bureaucracies suffer the same communication and productivity problems as government bureaucracies, against which conservatives rail. But they hope that inertia, employee goodwill, occasional breakthroughs, a good leader, and luck, combined with tax-breaks, restricted competition, and spendthrift consumers, will keep failure at bay. Most important, all companies compete against firms with similar problems.

As paranoid as executives must be, they survive in a back-slapping, extrovert culture that disavows pessimism. Not surprisingly, their fears focus on collective challenges. The New Left seemed a perfect existential threat. Civil rights and medicare had ideological enemies, but environmental and consumer regulations impact profit margins. Corporate boards and officers can accept the need to redress minority victimization; but advocates who turned consumers into enemies threatened entire revenue streams. “Unsafe at Any Speed”, Ralph Nader’s 1965 expose of auto manufacturers’ product safety problems, threatened an entire industry.

Activists like Nader saw businesses as having institutionalized problems that could be fixed. If the more radical considered the profit-motive immoral, more effective activists believed it worked if regulated. Companies need laws, like people do. Regulation can protect communities, rivers, and consumers, and promote a level business playing field. College students, however, notorious for youthful cynicism, often told pollsters they hated corporations. Given corporate culture’s stultifying image, rock and roll was definitely more attractive.

Effective activists combined with youth culture to stir corporate jungle paranoia, but big business overreacted because government was not on their side. GM responded to Nader’s auto safety book by attacking his character, using wiretaps and entrapment schemes. When that was revealed, GM President James Roche was forced to apologize to Nader in person, by a U.S. Senate subcomittee. It was one thing for a young Turk like Nader to write a diatribe about your product, but for the nation’s government to make the biggest Corporation in the world publically apologize was unheard of.

Large corporations used their own funds to ply politicians with demands, and got results. They used more money to fund business-oriented “think-tanks”, which put a media spotlight on conservative intellectuals. New conservative judges, like Robert Bork and Richard Posner, opposed the bipartisan antitrust regime, on neoclassical economic grounds. They claimed bigger can be better, because economies of scale reduce prices. They also believed monopolies and cartels that increase prices will face natural competition, which makes anti-trust regulation largely unnecessary.

This narrow economic focus on consumer costs avoids other monopoly impacts. Carefully fenced off as a concern of “competition economics”, only monopoly’s “inefficiencies”, its failure to “maximize utility”, has importance. But the national mood that forced passage of antitrust laws was hardly limited to prices; concentrated business damaged civil society, by controlling government. The U.S. political system is not an economic model, it’s a moral system transected by economic forces. The constitution’s framers used “divide and conquer” to control the convergence of interests and politics. Dividing up legislative capacity in different chambers, with complex rules and a separate executive, kept geographically distinct power centers in check. But from the Jackson administration on, concentrated economic power has spread well beyond regions. The trans-continental railroad, completed in 1867, marked a national footprint.

In the early 20th century, concentrated corporate power, in the form of trusts, unified single business sectors to control markets and politics. Antitrust law effectively removed some of this power, by breaking up sector monopolies. But over the next century, businesses began to organize across sector lines. Lewis Powell’s 1971 roadmap for business empowerment prioritized inter-sectoral centralization. “Independent and uncoordinated activity by individual corporations, as important as this is, will not be sufficient,” he wrote. Companies had to converge to get “the political power available only through united action and national organizations.” Powell advised the U.S. Chamber of Commerce to become the concentration point.

Where Woodrow Wilson had seen business power overwhelming government procedure in 1912, Lewis Powell claimed the reverse in 1971. The U.S. business executive was “forgotten” by government, according to Powell. To doubters, he suggested they try “the role of “lobbyist” for the business point of view before Congressional committees.” They’d find how little their point of view mattered, “in terms of political influence with respect to the course of legislation and government action.” To overcome this, unity of purpose must engage unity of action.

Hacker and Pierson trace how successful this strategy was. Most super-rich conservatives don’t care about abortion, gun control, gay marriage, or national forest use. They want lower taxes, fewer regulations, and the freedom to use their wealth as they wish. They finance opponents of pro-choice, gay rights, and environmental groups to keep a natural network of progressive humanitarians depleted, defensive, and unable to coalesce. This also builds a web of recalcitrant opponents of change, eager to play for pay, who can be deployed opportunistically.

Hacker and Pierson claim that the left’s weak reaction was initially due to political party democratization. Instead of back-room party potentates trading favors to agree on a candidate, politicians go straight to the people, in state-by-state primary campaigns. That puts activists, the most motivated local party members, into the driver’s seat. After the McGovern loss, politicians and corporate interests discovered a loop hole. Attack ads, televised in 30 second bursts, could smear an opponent’s reputation. Since primary audiences often have little information about prospective candidates, these negative messages sink in.

But Democrat party activists are hardly the reason business captured government, after McGovern. Although they undermined Carter’s reelection by mounting a primary challenge, Carter was more deeply damaged by conserative Democrats, some of whom voted for John Andersen, others for Ronald Reagan.

From Carter to Reagan, Clinton to Gore, and Bush to Obama, mass media has had much more influence on how the public perceives candidates that party activists. Expensive broadcast advertising is part of the media effect. Media companies themselves provide a lens that shapes or distorts political actors. They are integral to understanding recent change.

Along with the effect of political campaigns, Hacker and Pierson trace the left’s disarray to deunionization. The 1970s to 21st century time-lime contains labor’s slide, from representing 35% of full-time workers to less than 10%. Service and public employee unions have grown, but made up only a third of lost private sector union jobs. Unions represented workers with middle class demands, from reasonable wages to public education to health care. Without their substantive voice, the middle class has no cohesive voice, no heavy artillery to fight the right-wing’s big guns. Recent efforts in states like Wisconsin show the super-rich and their armies aren’t yet satisfied: they’ve set sights on collective bargaining.

According to Hacker and Pierson, unions must be reconstituted. They can once again stand for decent living conditions and middle class interests. Reunited, labor can counter-balance business concentration. Perhaps, but this supposes labor must match immense corporate wealth with equally immense organizational activity, a daunting challenge. Further, it’s based on turning back a clock to conditions unlike anything today.

The forces that would cause what Hacker and Pierson describe happening after 1970 were already present in those halcyon days of bipartisanship and union strength. Airplanes and aerospace, for transportation and the military, were the 1950’s most dynamic business sectors, yet they were spawned by World War II’s massive outlays. Small aerospace companies folded into larger corporations, and gradually migrated the west. They secured huge government contracts, sometimes their only customer. The Cold War was a boon, producing profits and innovation. The soft corruption of kickbacks, contributions, and post-government jobs with contractors got established. It spooked President Eisenhower, who devoted his presidency’s last, and most famous speech, to the “military-industrial complex”.

The intersection of business and government was in the Defense Department, not so much in Congress. But it caused American Cold War policy to veer to belligerence, whereas the country’s official strategy was peaceful containment of the Soviet threat.

Boeing and Teledyne had unions; their well-trained workers (in World War II or by the G.I. Bill) were too valuable. Other manufacturers adjusted to unions, too. Yet some, who manufactured less sophisticated hardware, resisted. GE, in particular, prevented labor organizers, not by hired goons who broke strikes, but by hired propagandists who captured workers. Unions focused on issues; anti-union propagandists talked about security and enemies. Employees need higher wages, but usually to purchase a lifestyle. Unions claimed they could get those wages, but propagandists claimed Unions destroyed lifestyles. Today’s devilishly deceiving campaign messages follow GE’s footsteps.

Sales people learn that consumers usually don’t buy things because of features, they seek something for themselves. Families don’t choose dishwashers because of dials and workmanship, rather, they seek fulfillment. That could mean finding order in family chaos, avoiding disgust by sanitizing mess, or adjusting one’s status by feeling superior to the neighbors. Unions offered better working conditions and salaries, but corporate research discovered workers seek independent identity. Too bad; like a software glitch, this proves to be a human weakness, one malevolent forces manipulate.